Project-Based Learning

Design meaningful, student-centered projects that promote collaboration, critical thinking, and real-world application of course content.

Project-Based Learning (PBL) is an instructional approach that engages students in exploring real-world problems and challenges through sustained, (often) collaborative projects. Rather than focusing solely on stand-alone papers or exams, PBL emphasizes active learning, critical thinking, and knowledge application - skills essential for success in both academic and professional contexts.

In higher education, PBL has been shown to:

- Enhance student engagement and motivation by connecting coursework to authentic tasks.

- Develop transferable skills such as teamwork, communication, and problem-solving.

- Improve academic achievement and deeper understanding of disciplinary content, according to multiple meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Faculty implementing PBL often report that students become more autonomous learners and demonstrate stronger integration of theory and practice. However, successful adoption requires thoughtful design, clear expectations, and structured support for both students and instructors.

While PBL is most commonly implemented through group or team projects to foster collaboration and interpersonal skills, it can also be designed for individual learners (Thomas, 2000; Bell, 2010). Individual projects are often used in capstone courses, honors programs, or graduate-level work where independent inquiry and personalized outcomes are prioritized (Balleisen et al., 2023). The choice between individual and group formats depends on learning objectives, course size, and disciplinary norms (Zhang and Ma, 2023)

Theoretical Foundations of PBL

Project-Based Learning is grounded in constructivist learning theory, which posits that learners build knowledge actively through experience and reflection rather than passively receiving information (Dewey, 1938; Piaget, 1970). PBL operationalizes this by situating learning in authentic contexts where students engage in inquiry, problem-solving, and collaboration. Key theoretical underpinnings include:

These frameworks collectively support PBL’s emphasis on authenticity, collaboration, and reflection, making it a powerful approach for fostering deep learning and transferable skills in higher education (Thomas, 2000; Bell, 2010).

Recent Scholarship on PBL

Recent studies focused on PBL provide evidence of its impact on student learning and faculty practice:

Collectively, these insights underscore that PBL is not only a high-impact practice for students but also a rich area for scholarly inquiry into effective teaching strategies.

Benefits and Challenges of PBL

Benefits

Enhanced Engagement and Motivation

Students often report higher interest and persistence when working on authentic, real-world projects (Bell, 2010).

Development of Transferable Skills

Beyond disciplinary knowledge, PBL cultivates collaboration, communication, leadership, and project management abilities (Balleisen et al., 2023).

Deeper Learning and Retention

Meta-analyses show improved conceptual understanding and long-term retention compared to traditional lecture-based methods (Zhang and Ma, 2023; Rehman et al., 2024).

Positive Attitudes Toward Learning

PBL encourages autonomy, resilience, and confidence in tackling complex problems (Chang et al., 2024).

Integration of Theory and Practice

By situating learning in authentic contexts, PBL bridges the gap between academic concepts and practical application.

Challenges

Time and Resource Demands

Implementing PBL requires substantial time for planning, mentoring, and assessment (Eshankulova and Nurtidinova, 2024).

Assessment Complexity

Evaluating both the process and final product in PBL is challenging (Fernandes et al., 2005).

Group Dynamics Issues

Unequal participation and poor communication can undermine group effectiveness (Hussein, 2021; Gordon, 2023).

Scalability Concerns

Scaling PBL in large university classes presents logistical challenges (Shi and Li, 2024; Gortalova et al., 2019)

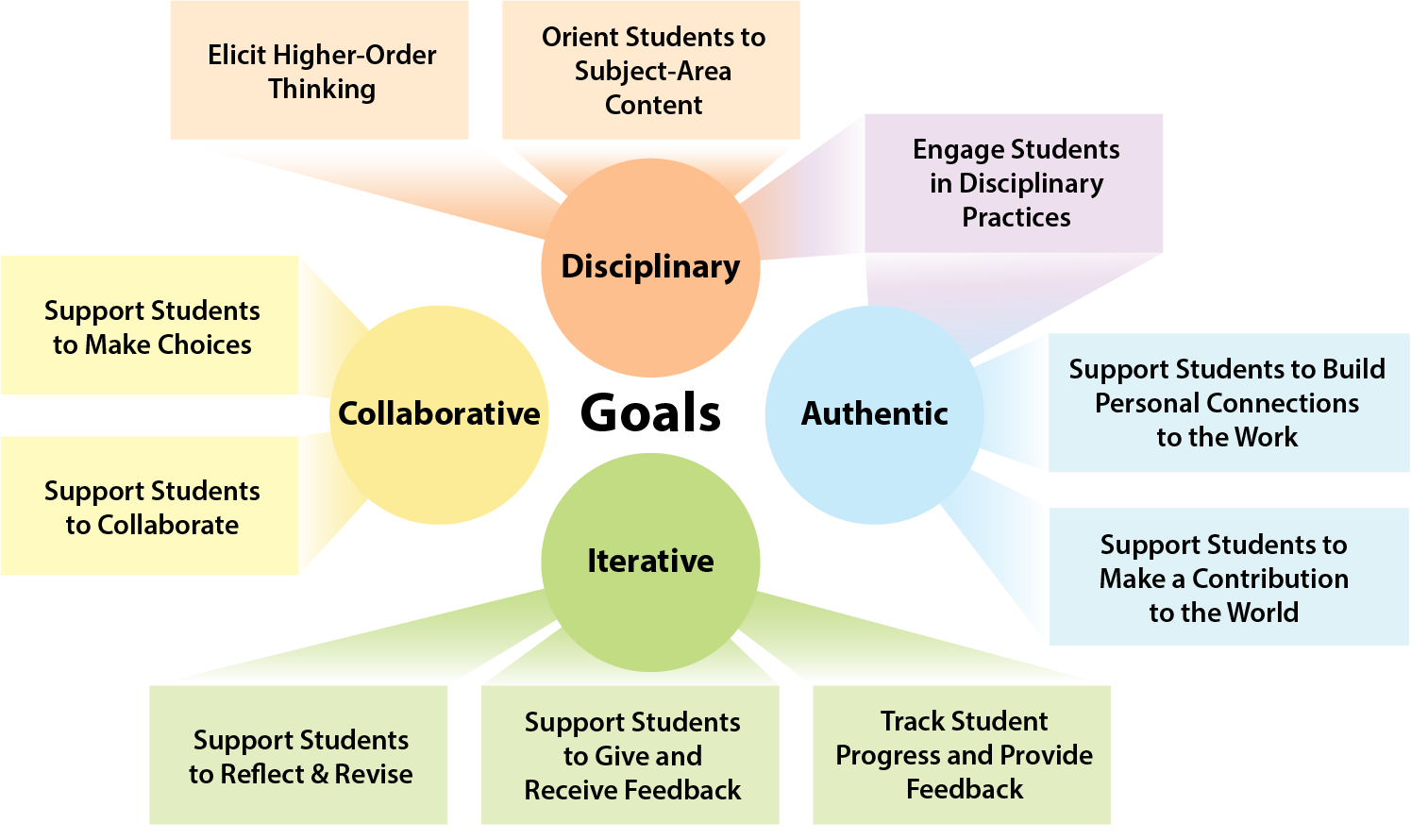

Key Elements of PBL

PBL has four key elements: disciplinary learning, authentic work, collaboration, and iteration (Grossman et al., 2019). These elements enable deep engagement with a topic over a sustained period of time. This diagram describes the necessary steps instructors should take to design robust PBL assignments. It is based on the work of Penn GSE—their resource on PBL has extensive information about each of these steps, including questions to ask yourself as you’re designing these types of assignments.

Adapted from the work of Penn GSE

-

Disciplinary

- Elicit Higher-Order Thinking

- Orient Students to Subject-Area Content

-

Disciplinary and Authentic

- Engage Students in Disciplinary Practices

-

Authentic

- Support Students to Build Personal Connections to the Work

- Support Students to Make a Contribution to the World

-

Collaborative

- Support Students to Make Choices

- Support Students to Collaborate

-

Iterative

- Support Students to Reflect and Revise

- Support Students to Give and Receive Feedback

- Track Student Progress and Provide Feedback

Practical Tips for Implementing PBL in Course Design

Examples of PBL Assignments Across Disciplines

Disciplines

-

Engineering

Design and prototype a sustainable energy solution.

-

Business

Develop a comprehensive marketing plan for a startup.

-

Health Sciences

Create a patient education toolkit for chronic conditions.

-

Computer Science

Build a functional web application addressing a social issue.

-

Education

Design an interdisciplinary curriculum unit.

-

Environmental Studies

Conduct a field-based project analyzing local water quality.

-

Humanities

Curate a digital exhibit on a historical theme.

References

Bell, S. (2010). Project-Based Learning for the 21st Century: Skills for the Future. The Clearing House, 83(2), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505415

Balleisen, E. J., Howes, L., and Wibbels, E. (2023). The impact of applied project-based learning on undergraduate student development. Higher Education, 87, 1141–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01057-1

Chang, C., Choi, J., and Şen-Akbulut, M. (2024). Enhancing student engagement through authentic contexts in project-based learning: A mixed-methods study. Education Sciences, 14(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020168

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan.

Eshankulova, N., and Nuritdinova, S. (2024). Implementing project-based learning in university courses: Challenges and opportunities. World Bulletin of Social Sciences, 12(1), 9-15. https://scholarexpress.net/index.php/wbss/article/download/3765/3199/6811

Fernandes, S., Flores, M.A., & Lima, R.M. (2012). Student assessment in project-based learning. In: Campos, L.C.d., Dirani, E.A.T., Manrique, A.L., & Hattum-Janssen, N.v. (Eds.) Project approaches to learning in engineering education. SensePublishers, Rotterdam. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-958-9_10

Gordon, R. (2023) Resolving team conflict in your classroom projects. American Public University. https://www.apu.apus.edu/area-of-study/education/resources/resolving-team-conflict-in-your-classroom-projects/

Gorlatova, M., Sarik, J., Kinget, P., Kymissis, I., & Zussman, G. 2019). Project-based learning within a large-scale interdisciplinary research effort. Australasian Journal of Engineering Education, 25(2), 89–101. https://arxiv.org/abs/1410.6935

Grossman, P., Pupik Dean, C. G., Kavanagh, S. S., and Herrmann, Z. (2019). Preparing teachers for project-based teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 100(7), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721719841338

Hussein, B. (2021). Addressing collaboration challenges in project-based learning: The student’s perspective. Education Sciences, 11(8), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080434

Kadel, R., et al. (2021). Multi-modal assessment strategies for PBL. Journal of Education and Learning Sciences, 1(1), 567–582. https://www.springfieldresearchuniversity.net/_files/ugd/6b1e99_550d9820246e4b85b376d3f258455ae2.pdf

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Lu Zhang, and Yan Ma. (2023). Meta-analysis of project-based learning effectiveness in higher education. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1202728. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1202728

Miao, Y., et al. (2024). Institutional strategies for scaling PBL. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 21(3), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241276600

Piaget, J. (1970). Science of Education and the Psychology of the Child. New York: Viking.

Rehman, N., Huang X., Batool, S., Andleem, I., & Mahmood, A. (2024). Assessing the effectiveness of project-based learning: A comprehensive meta-analysis of student achievement between 2010 and 2023. ASR CMU Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJASR.2024.015.

Shi, Y. & Li, W. (2024). Empowering education: Unraveling the factors and paths to enhance project-based learning among Chinese college students. Sage Open 14(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241276600

Thomas, J. W. (2000). A Review of Research on Project-Based Learning. Autodesk Foundation. http://www.bobpearlman.org/BestPractices/PBL_Research.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Zhang, L, & Ma, Y.. (2023). A study of the impact of project-based learning on student learning effects: a meta-analysis study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1202728. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1202728

Written by David Giovagnoli Assistant Director for Scholarly Teaching and Learning, Center for Integrated Professional Development, Last Updated 10/24/25